- Home

- Tony Duvert

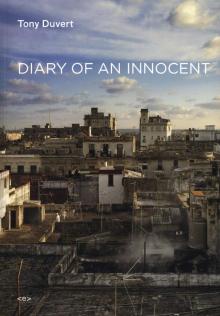

Diary of an Innocent

Diary of an Innocent Read online

“I always write completely nude, and I don’t wash before, ” writes Tony Duvert, whose explosive Diary of an Innocent is part tract, part porn, part theory, part fiction, and (I presume) part fact. Certain pages of Gide, Genet, Hocquenghem—and certain scenes from Bresson or Pasolini—suggest themselves as mild precursors, but Duvert goes further, filthier, faster. Only the Marquis de Sade outpaces him. Must we burn Duvert? I pray not. This book, troubling and memorable, interrogates—with delicate strokes—the damaged state of contemporary sexual relations.

—Wayne Koestenbaum

Written with gusto and infused with a luminous bitterness, this novel is more disturbing today than it was when first published in French in 1976. In his openly declared war on society, Duvert presents a worldview that offers no easy moral code and no false narrative solution of redemption. And yet no one will remain untouched by the book’s dazzling language, stinging wit, devotion to matters of the heart, and terse condemnation of today’s society.

Available in English for the first time, this poetic, brutally frank and outright shocking novel recounts the risky experiences of a sexual adventurer among a tribe of adolescent boys in an imaginary setting that suggests North Africa. Diary’s cascading portraits of the narrator’s sexual partners and their culture ends with a fanciful yet rigorous construction of a reverse world in which marginal sexualities have become the norm.

“Diary of an Innocent by Tony Duvert is a truly scandalous work, but first and foremost a work of great depth and freedom... A book that reinvents the seduction of literature.” —Abdellah Taïa, author of Salvation Army

Tony Duvert (1945–2008) is the author of fourteen books of fiction and nonfiction. His fifth novel, Strange Landscape, won the prestigious Prix Médicis in 1973. Exiled from the French literary circles that once adored him, Tony Duvert’s life ended in anonymity in 2008 in the small village of Thore-la-Ftochette where he had been living a life of total seclusion. Other books translated into English include the nowel When Jonathan Died and the scathing critique of sex and society Good Sex Illustrated.

SEMIOTEXT(E) NATIVE AGENTS

distributed by The MIT Press

ISBN: 978-1-58435-077-4

SEMIOTEXT(E) NATIVE AGENTS SERIES

“Cet ouvrage publié dans le cadre du programme d’aide à la publication bénéficie du soutien du Ministère des Affaires Etrangères et du Service Culturel de l’Ambassade de France représenté aux Etats-Unis.”

This work, published as part of the program of aid for publication, received support from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Service of the French Embassy in the United States.

This edition Semiotext(e) © 2010

© 1976 by Les Editions de Minuit in, 7 rue Bernard-Palissy, 75006 Paris.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Semiotext(e)

2007 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 427, Los Angeles, CA 90057 www.semiotexte.com

The translator is profoundly thankful to Carole Sabas and Laurence Viallet for their help.

Special thanks to Dennis Cooper, Marc Lowenthal, Abdellah Taïa, Robert Dewhurst and Alice Tassel.

Cover art by Stan Douglas, Rooftops, Habana Vieja, 2004.

C-Print mounted on 1/4 inch honeycomb aluminum, 31 × 38 3/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery.

Design: Hedi El Kholti

ISBN: 978-1-58435-077-4

Distributed by The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. and London, England Printed in the United States of America

DIARY

OF AN INNOCENT

Tony Duvert

Translated from the French

and with an introduction

by Bruce Benderson

Bruce Benderson

Innocence on Trial: The Politics of Tony Duvert

Literally, the “innocent” to whom the title of this novel refers only makes an appearance at the very end of the book. He’s a sweet, dimwitted street boy who is fascinated by the narrators typewriter and spends long periods of time typing every letter of the keyboard in order, over and over. Jokingly, the narrator considers handing in the boy’s work, rather than his own, as the manuscript for the book but realizes that few would read it. Nevertheless, he asks himself, “Is there a law that is so different in the series of words that I put down?” Such comparisons and contrasts between the illiterate and the literate, the amoral and the moral, the impoverished and the well-to-do, and the individual and the family are the mechanisms that drive this narrative. But the real “innocent” to whom the title of this novel refers is the narrator himself, an unnamed lover of boys living temporarily in an unnamed southern city that suggests North Africa of the 1970s. This shouldn’t, however, lead to the conclusion that the word “innocent” is being used ironically. Or rather, if it is, that irony is at our expense, rather than that of the protagonist’s or author’s.

Those familiar with the other writings of Tony Duvert (1945–2008) or his public reputation are bound to conflate the fictional experiences recounted in Diary of an Innocent with his own. However, during the years in which he enjoyed notoriety as a literary figure (1969–1989), he never publicly clarified his own sexuality, despite the fact that he made his politics surrounding the issue of sexuality absolutely clear. His critique of French bourgeois life seen through the lens of sexuality was as acerbic as it was tireless, and much of it targeted initial repressions and exploitations of sexual energy during the period of childhood. As he explained at length in his nonfiction book, Good Sex Illustrated, those cultural institutions we sanctify the most—the rearing of children, education, the family, our legal and medical systems, the clergy, marriage—are actually accomplishing the very opposite of what they claim. The raising of children, as he sees it, is a ruthless commandeering of their impulses and the capitalization of their bodies by an enslaving process of marketability. In this system, mothers are no more than low-level meat factory managers, who serve as the overseers of the sacrifice of childhood to the capitalist packaging conglomerate we call decency; fathers are trained to take out their frustrations through oedipal vectors in order to geld their children before they have become fully aware of their own capacity for pleasure; teachers are hypocritical lackeys whose sole occupation is to rein in children’s polymorphous creativity and to provide convincing rationalizations for its reshaping into obligation; doctors, psychiatrists and priests are there to stamp such processes with legitimacy. And finally, the sole purpose of marriage is to repeat this inescapable cycle by creating more upholders and defenders of it. The narrator in Diary of an Innocent serves quite obviously as a mouthpiece for these politics. For Duvert, the promiscuous boy lover has become the most convenient device for taking pot shots at our social order.

So much for the narrator, but what about the succession of street boys in the novel who serve as his love objects? Almost all of them are wayward prepubescent panhandlers or child laborers from the petit bourgeoisie and working classes. Most tend to enjoy a high degree of autonomy in the streets outside the family circle. All have relationships with parents or elder siblings that are characterized by neglect or violence. Certainly, we expect the author to be calling attention to their plight. However, Duvert demonstrates quite convincingly that—even given such conditions—these boys are in a position that any French middle-class child should consider enviable. This is because the street boys enjoy full ownership of their bodies and their time whereas the average protected French child is taught to be a robotic tool of parents, teachers and priests.

This is not to claim

that, when the novel enters the homes of some of these street boys, their parents and older siblings aren’t portrayed as frankly tyrannical. But Duvert goes out of his way to attach such behavior to the reality of poverty and to the rigid, simplistic, traditional codes of the culture he is describing. What mitigates the bad behavior of these particular caregivers is their directness, the fact that their actions lack the hypocrisy and hidden motives of the same kind of treatment when it occurs in a bourgeois context. In taking these positions, Duvert’s radical project essentially involves turning our moral code upside down, so that the alienation and sexual tastes of the narrator resemble innocence and sincerity whenever they are compared to those of the normal bourgeois literary audience who will become his readers and whom he is attacking.

The narrator in Diary of an Innocent functions as a test case for someone who attempts to avoid—however abjectly—the oppression of social institutions. His position is one of complete alienation from every element of society that Duvert has defined as hypocritical. He lives without family, without concern for his own safety or health, without allegiance to his own country and without the sexual orientation and sobriety we would expect from someone of his level of education and class. He is “innocent” of all those things and thus completely at odds with the social order. Rather than being a member of a political group or movement, he is single-handedly opposed to the capitalist cultural machine that produced him. This does not imply, however, that he is a firebrand, fighting for justice and attempting to convince others that he is in the right. As an “innocent,” he seeks merely to live his life in as unfettered a way as possible.

Despite all of this, one is occasionally—and erroneously—led to believe that Duvert is a kind of activist. One of the most striking devices in this complicated narrative is a section that fantasizes obsessively about what it would be like if homosexual pedophiles were considered the norm and heterosexuals were treated the way homosexuals were in the era of pre-Stonewall. So fastidious is Duvert in covering every element of reversed oppression that could occur that this section becomes a hilarious send-up of the child protection schemes and exclusion of homosexuality from daily life that prevailed in Western society in the middle of the twentieth century. As each prohibition and each prejudice is piled on, all of them begin to seem more and more absurd, producing delightful satirical effects. But once this reverse dialectic is accomplished, Duvert deflates it immediately by pointing to a central flaw in his argument: no homosexual, he explains, would ever oppress another group to the level of exclusion and isolation to which the homosexual himself has been pushed. Thus, the purpose of this upside-down narrative is not to produce change, but merely to sharpen our consciousness of the mechanisms of the social order, and such a process of analysis promises to lead most of us into a profound state of uneasiness.

What American readers will find most repulsive about this novel is the fact that it isn’t redemptive. In order to understand the importance of the theme of redemption to the American scene, we must first briefly discuss the influence of seventeenth-century Puritan literature on the roots of the Anglo-Saxon literary tradition, and the about-to-be-born novel of the century that followed. Especially in its early stages, the novel in Anglo-Saxon cultures was deeply influenced by the spiritual autobiography, which had already become a favorite form of reading. Perhaps the best known of these spiritual autobiographies is John Bunyan’s Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners (1666), in which Bunyan recounts his lapses into sin that lead eventually to his epiphany and conversion. In such a book, the journey from point A to point B—from damnation to grace—created a ready-made linear narrative that always enjoyed the same structure. It is a movement from error toward conversion and the proverbial “happy ending.” And it suggests that no story is worth its salt, or perhaps, no story could be called a story at all, unless the protagonist is brought back into the fold. Although this fold may have originally denoted a relationship only to God, it has taken on more banal and conformist parameters in modern times. One could almost substitute “family” for “fold.”

Today there are thousands of fiction and nonfiction books that are constrained by the pattern established by narratives like Grace Abounding. Depictions of transgressions may be limitless, accounts of sensuality and appetite luridly graphic, the altered states of drug abuse described to a T, but we always end up in a recovery meeting, which we then realize is our perspective for looking back, and which wins us, hopefully—if we are authors—a guest spot on Oprah.

By saying this, I am not claiming that we do not also enjoy narratives that end in tragedy rather than in a happy ending. But these tragic narratives are, as well, adapted to the mold of redemption. In every case, the tragedy serves as a kind of punishment, and since the book is being written from a post-punishment perspective, the narrator is finally established as “good,” having gone beyond error (even if it was too late in his or her particular case) and therefore worthy of our attention. As an extreme but relevant example, I must point out that our literary tradition has no narratives about pedophiles who avowedly enjoy behaving in a manner they admit we would see as having bad intentions. They are either confessing an illness to us or trying to prove that their orientation really is well meaning and socially constructive, usually in the sense most accepted by the middle-class mind.

Duvert, on the other hand, who remains very close to his narrator in this novel, doesn’t wish to be thought of as contributing to the well-being of society, which he sees as a machine of speciousness. He makes a strong claim of being absolutely irredeemable in our eyes, salting this negation with a brazen claim to innocence. And indeed, in a way that may seem perverse to some readers, he locates the moral superiority of his text in its absolute irredeemableness. He forsakes the only two possible approaches to this subject that an Anglo-Saxon might choose: “coming to his senses” and realizing the error of his orientation, with the narrative representing the journey to that realization; or settling on a way to convince us that his life-style is for the betterment of society. Duvert’s character, on the other hand, is “lost” to our notion of what is good or right, and he chooses to stay that way for the very purpose of declaring himself innocent. He may be “lost,” but if that is the case, its not because he has chosen the wrong path and is lost to himself, but because he has been abandoned by the social order, something he has litde hope of changing.

Duvert belongs, of course, to a well-known tradition of French pokes maudits, who aligned themselves with variations of the notion of evil and who include Sade, Baudelaire, Bataille, Huysmans and Genet. The fact that many passages of Diary of an Innocent were repulsive to me and that I identified that repulsion as much more than a matter of taste is merely proof of the efficacy of Duvert’s purpose. Several scenes are there mostly to ensure a portrait of the protagonist as someone who is plainly repugnant to the normal reader. In one, he removes a tiny worm from his anus with the tip of a knife as if it were light comedy; in another, he devotes almost an entire page to describing a cat munching on a giant cockroach as he speculates about how it might taste and compares that taste to elements of French cuisine; in a third, he recounts an attempt to have coitus with a dog during a camping trip when he ended up in a French town that felt alien and rejecting to him.

Even in France, discussions about or with Duvert have tended to touch upon the startling amount of aggression and alienation in his texts. In both his writing and the interviews with him, it is almost as if he were jumping the gun and expressing his disgust for those who would express theirs for him—as if he has left any call for inclusion by the wayside long ago and has made himself a sacrificial victim of social rejection. But for what purpose? One could say he has chosen to lie down with the Devil in order to escape the narrow boundaries of social experience—and thus achieve an unusual kind of transcendence. As I have tried to show, such a stance probably could not be more foreign and more distasteful to the American mind, which tends to function on the assumption

of conformity and inclusion. (There’s room for everybody, if only we can learn to understand!)

There may also be one other purpose of Duvert’s narrative, though evidence for it is subtle. I would call this de-idealization. Idealization of human behavior is a tactic all of us use to survive. A most obvious example of this is our reluctance in almost any discourse (excluding vulgar satire) to discuss or provide examples of certain activities we engage in regularly, such as defecation. When we see a beauty queen on television gushing over the receipt of a rhinestone crown and a bouquet of long-stemmed roses, it is true that some of us may in our minds subject her to a prurient sexual objectification, but the furthest thing from our thoughts is what she looks like on the toilet or menstruating. Why? Not only does the frequency of both make them an integral part of human life, they also preoccupy all of us to a high degree at moments when we’re alone.

As a child, I remember a transgressive game I would play compulsively with myself: I would think of friends of my parents, teachers, politicians, alluring actresses or any individual who encouraged idealization and radiated social power; and then I would try to visualize the same person on the toilet. After questioning friends, I have come to the conclusion that such perverse fantasizing is far from original. To see authority, beauty or other social currency suddenly disappear the moment one adds certain universal but private behavior to the repertoire of the imagination can become positive exploration for a child who has just begun to confront the world and its intimidating institutions.

Duvert’s intention in this text may be analogous. Not only is he forcing the grotesqueries of his own libido upon us; he is also calling for a de-idealization of our experience and human experience in general. Hidden behind his rather boastful descriptions of situations that threaten to turn our stomachs is the challenging question: And how pretty would you look with your soul bared to this extent?

Strange Landscape

Strange Landscape A Silver Ring in the Ear

A Silver Ring in the Ear When Jonathan Died

When Jonathan Died Diary of an Innocent

Diary of an Innocent